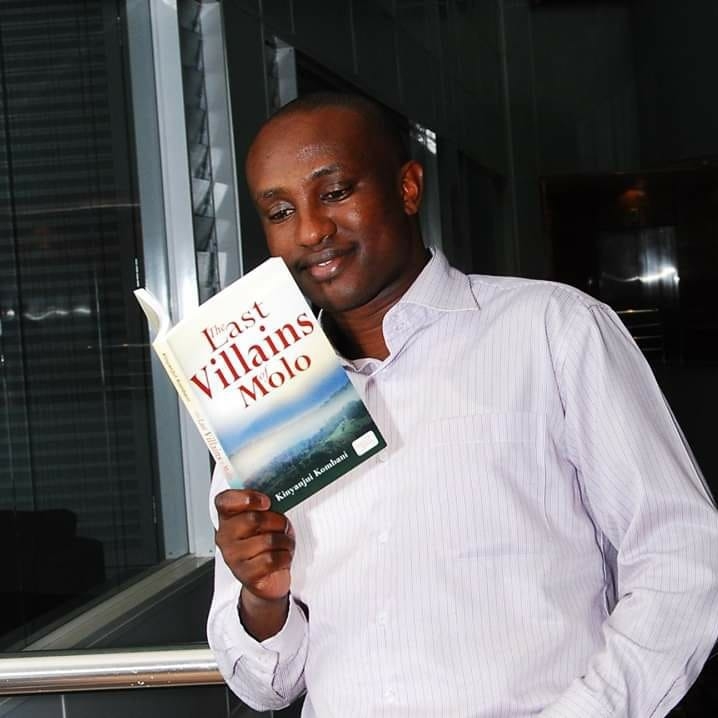

- Maisha Yetu: Congratulations on your book turning 20. What does this milestone mean to you?

Kinyanjui Kombani: Wueh! How time flies!

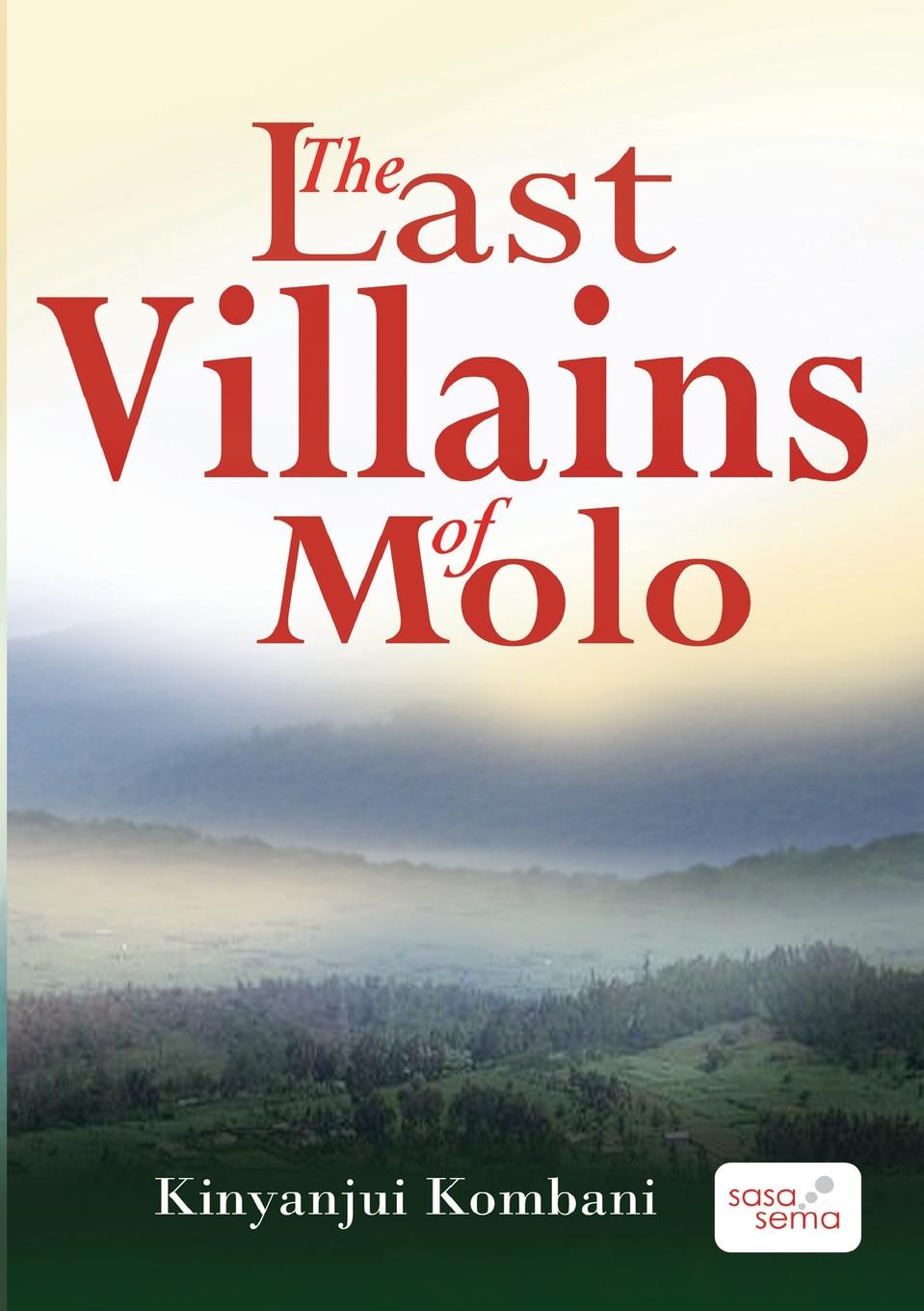

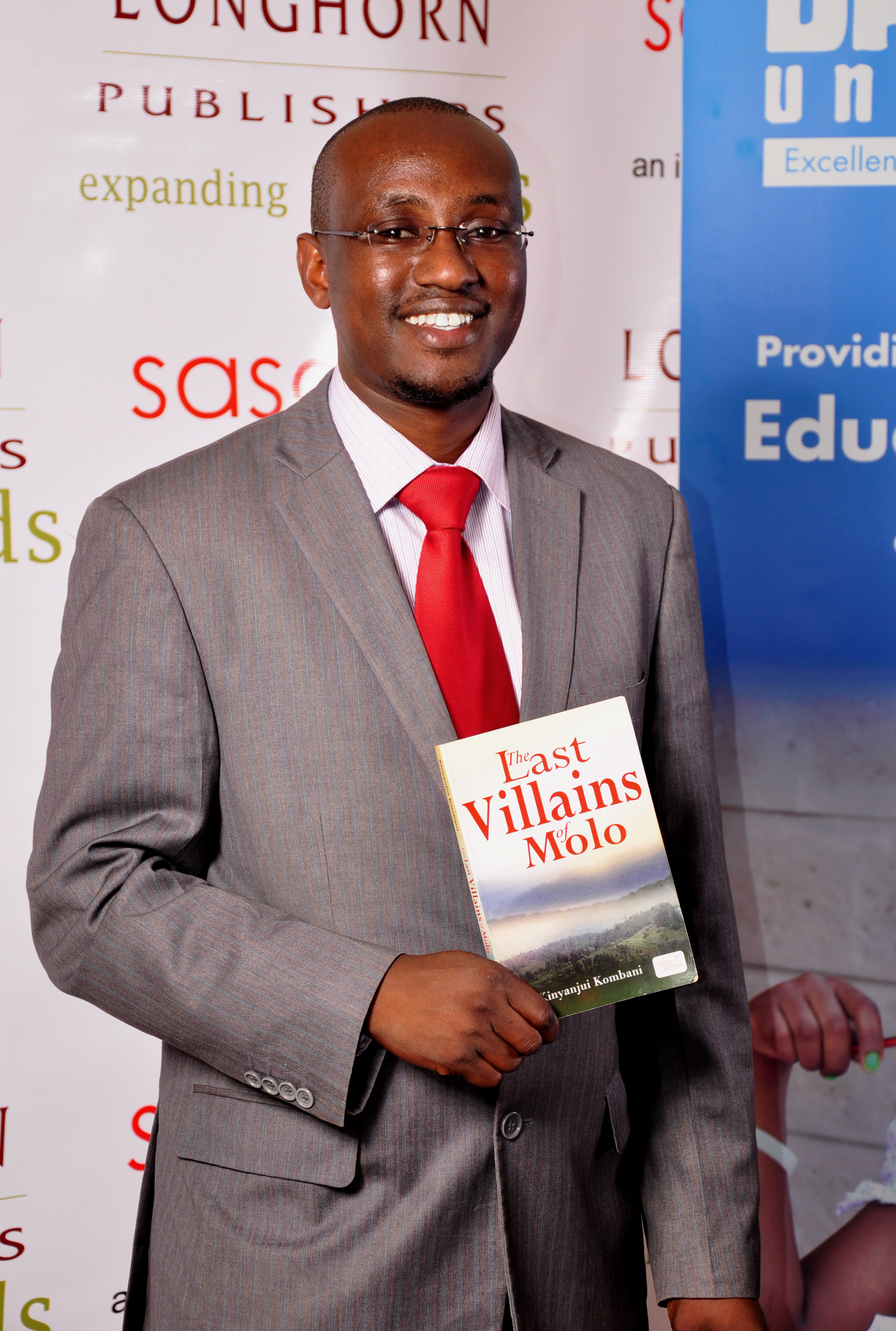

First, it is an opportunity to reflect on my own writing and publishing journey. Life moves so quickly that we forget about how far we have come. When I wrote the book, all I wanted was to see it on a shelf at a bookshop — specifically, at the now-closed Bookpoint, on Kenyatta Avenue. They had book dummies displayed as you passed by the shop, and I couldn’t wait to have mine up there, with the rest. To have ‘The Last Villains of Molo’ become part of a national conversation – mentioned as one of the top Kenyan books of all time and studied in schools and universities – that was not part of the plan!

Secondly, it grants us, as Kenyans, the opportunity to think harder about our future. 20 years is a long time to rethink our national politics and the accumulated impact of the politics of division. For me, this milestone means giving a lot more reflection to where our country is heading. Most of the issues I addressed in the book – tribalism, poverty, mob justice, extra-judicial killings, politically instigated ethnic strife, and more – remain constants. How long shall we allow our leaders to sow the seeds of discord among us?

- Your dream of becoming a published author with The Last Villains of Molo was almost thwarted despite it being ‘published’ with glowing reviews in the papers; tell us more about this trying episode for you…

Yes. Although the book was released in 2005, it was not made available until 2008 when we had a formal book launch at the Alliance Francaise. It was missing from the bookshelves years later and, frustrated at seeing my dreams shattered, I started shopping for a new publisher. Luckily, my first publisher did not resist the withdrawal request, only insisting that I buy all the books in stock. The book was re-released by Longhorn Publishers under a new cover. And the rest is history.

Like I said, I never thought my book was going to be as big as it became. It was my first publisher who suggested that it had the potential to be a school text. When he asked me what I would do if I got millions in royalties, my dream of a LandCruiser VX was born!

- When you wrote the manuscript for this book you were a university student, with no access to a computer, let alone a typewriter, what was it that kept your dream alive when others would have thrown in the towel?

I lived with my brothers in Ngando, a sprawling estate behind Ngong Road in a single roomed house (this was the setting of ‘Villains’). We didn’t have most of the resources that are available to us now – cyber café charges were 10 shillings a minute!

I got help from my neighbours and friends – the Mudola family. They had a cyber café in Langata and would allow me to use their computer when there were no clients. In fact, the bulk of the manuscript was typed by Dorothy Mudola. She believed in the story and wanted to see it come to life.

I also had great encouragement from my mentor David Mulwa. He had read the initial handwritten manuscript and wrote “This is a masterpiece! Have it typed and submitted for publishing.” He kept asking about the progress, so I had to keep at it. The late Gachanja Kiai, one of my other lecturers who read my initial stories, and who introduced me to the publisher, was also following up on progress.

The publisher accepted the manuscript on condition that I rewrite a huge part of it. We had to get rid of about a third of it (which explains why a part of the book felt rushed – spoiler alert “Stella”). But by this time the cyber café at Langata had been closed and I was about to lose the publishing opportunity. I managed to slide past the then Kenyatta University Vice Chancellor Prof George Eshiwani’s security and told him of my plight. He turned to his personal assistant and instructed her to let me have all the support I needed. From that day, I had access to three secretaries – I would write the manuscript at night and submit it to them in the morning for typing. That is how I managed to beat the deadline.

- You were probably the very first Kenyan writer to address the thorny issue of ethnically instigated clashes, what fired this zeal?

We lived in Molo until 1995 when I went to boarding school in Form 1 and then moved to our ancestral home in Njoro. We were to later meet the family of Mzee Joseph Mbure who had been displaced from Kamwaura in the 1997 clashes. My grandmother had given them a house and some land to till until they could move back. I heard the old man’s recollections about the clashes. Later on, I went to the Nation Centre Library where I discovered, to my horror, that his stories were factual. The Last Villains of Molo started out as a short story but grew into a full length novel.

We lived in Molo town during the 1992 clashes. One of my brothers was walking in town with my sister when he was hauled into a lorry to go fight in the forest. I was at the Molo hospital when a man was brought in with an arrow lodged in his forehead. One of our teachers, a Kalenjin, asked one of my brothers to take care of his house while he left town when the situation became untenable. All these are incidents that made it into the novel.

When I went to university, I discovered that my roommate had also experienced the clashes in Molo. He gave me harrowing descriptions about surviving the clashes by sleeping in fields of napier grass.

I felt that these were stories that needed to be told, fictionally. And nobody was telling them.

- We are two and half years to the 2027 General Elections and we’re already hearing inciteful ethnic rhetoric from politicians, are Kenyans that forgetful, despite the outcome of the 2007 election, that landed some politicians at the International Criminal Court?

I don’t think Kenyans are forgetful. We all remember our collective suffering – not only from the 1992 clashes, but from all clashes that have happened every election period. The problem is that we have allowed our politicians to continue to use us for political expediency. We have allowed them to keep using the same tribal rhetoric, spiced with words like ‘murima’ and ‘madoadoa.’ And the resurgence of the Mungiki, spurred on by obvious political patronage by our leadership, spells even more danger.

But then, we have a more enlightened youth who have no more allegiance to tribe. Conversations on social media are mostly about issues. I quoted David Mulwa in the novel: “The young refuse the bonds of the past, the bonds of hate.” And I think this is going to be true in the coming years. Gone are the days when we allow ourselves to see the enemy as tribe X or Y. And people are quick to call out politicians.

I think we have a better-informed electorate, and in the future, we will be able to vote in leaders who do not preach violence. I will be surprised if these war mongers come back to power.

- What are some of the milestones this book has enjoyed and what it has done to you as an author?

Man! Where do I start?

I constantly receive messages on social media from people who have read and being impacted by the book. This for me is a huge motivator to keep writing.

The book has also been studied in schools and at university level. I receive may queries from people who are studied it and who are stuck in one way or the other. I am not of much help, sadly, what with topics such as “Literary Historiographical Analysis of Kinyanjui Kombani’s The Last Villains of Molo’! See – when I write I just want to tell a story. Historiographical analysis – whatever that means – is not part of the plan!

The book was mentioned in The Guardian as one of the top 10 books about Kenya. It has been mentioned in other Top-Something lists. We have optioned the book for film production. However, it has yet to gain a commitment for a film budget. We keep looking!

As a writer, I must confess that it was a hard act to follow. I had put my heart and soul into it, and I didn’t think I had any other story in me. It was more than five years later that I could attempt a second novel – Den of Inequities – which also did well.

Early success in my career meant that I could experiment with different ideas, hence the shift to faster-paced, simpler and definitely not darker books like ‘Of Pawns and Players’ and ‘Hawkers-Pokers’. My writing style is now much more different.

- You recently took to Facebook to shop for ideas on how to celebrate this 20-year milestone, you must have received plenty of them by now…

Yes, I reached out to my connections on social media for ideas on how to commemorate the milestone – because the book is a success thanks to them. I received dozens of ideas within a few hours.

Some of the ideas we are going with is a release of a reading of an excerpt of the book by my friend and mentor, the legendary John Sibi-Okumu, OGW. JSO will also be reading other excerpts live in March.

On 21 February 2025. we will be having a Readers’ Special Space on X / Twitter featuring appearances by people who have been part of the novel – from those who inspired it to those who have taught it at high school/university level, to those who have read it for fun. We will also have a slew of other X Spaces to reflect on Kenya’s tumultuous history, and the challenges ahead of us.

Additionally, there are commemorative articles to be published across the media houses and two special radio shows. We will have virtual panel conversations with other writers who have handled ethnic conflict in Kenya, in addition to live Ask-Me-Anything sessions on Tiktok, Facebook and Instagram. I am excited at the lineup of people who have raised their hands to be part of this conversation.

We are also working on exciting giveaways in collaboration with Nuria Books and Longhorn Publishers.

- You are also known as the ‘banker who writes’, how do you combine the two roles?

First, I am glad to work with a company that allows me to use my talent as a writer. This is not a luxury enjoyed by most creatives. There are lots of interdependencies between the two careers – I believe I am a better writer because I am a banker, and a better banker because I am a writer. In my role as a Learning & Development specialist, I get to use my creativity to design, develop and deploy learning solutions. And when it comes to building my brand as a writer, I borrow a leaf from the bank, especially with the need to have a greater purpose. Finding my ‘why’ helps to refine my ‘what’ and ‘how’, and helps me to prioritise what is of greatest impact to my purpose. I constantly ask, as our head of Strategy and Talent does, “What is this in service of”?

Secondly, I do not want to pretend that it is easy. Working in a global role in an international bank means that I must make a lot of sacrifices so as not to drop the ball. You also don’t want anyone to think that any ball is dropping because of my other activities.

I see it as priorities management rather than time management. For me, this means that when I am working in the bank, I give it 150%, and when I can make time for writing I get rid of other distractions. I have to choose what I am saying yes to, more carefully, because it means saying not to conflicting agendas.

- Ever since the publication of The Last Villains of Molo, you have enjoyed quite the ride as a writer, winning literary awards in the process; take us through that…

I was shortlisted for the 2005 Rhodes Scholarship and won the ‘Outstanding Young Alumni Award’ by Kenyatta University in 2014. In 2015, I was named in the Top 40 Under 40 Business Daily Africa Award and a ‘Top 5 Under 35 Award’ at Standard Chartered Bank (an award to recognize the most outstanding colleague under 35 years).

In 2017, I was shortlisted CODE Burt Award for African Young Adult Fiction for Finding Columbia, which went on to win the 2018 African edition and is now a school text for Grade 7. I was also a national finalist for my books Do or Do and Eve’s Invention. This is the first time a writer had been a double finalist in the national edition of the Burt awards.

In 2019 my book Of Pawns and Players won the Wahome Mutahi Literary Award. In the same year, ‘Do or Do’ won the Jomo Kenyatta Prize for Literature, Youth Category. These are considered Kenya’s most prestigious literary awards, and this has been great for me.

I have also been invited to be part of Nairobi Noir – an anthology excavating the history of Nairobi, as seen through the eyes of its dwellers. I was also involved in ‘Toto Tales/Fabulous Four’ a children’s series, The Kenya Yearbook Editorial Board-commissioned project to create a children’s version of their popular Kenya Yearbook.

- Emerging writers moan about limited opportunities for getting published, hence the rise of self-publishing in Kenya, what are your thoughts on this phenomenon?

Upcoming writers have always had a challenge getting published by traditional publishers. I blame this on the way the publishing industry is set up, with majority of sales coming through school texts. The result of this is that publishers go for writers and books that are most likely to make it through to the school curriculum, with little to no investment in books for leisure reading. Those of us who manage to crack through the brick wall are the exception rather than the rule. And even then, we have to wait years for publishing diaries to align.

The good news is that there more opportunities for self-publishing. A lot of professionals have emerged to offer services such as editorial consulting (John Sibi-Okumu, Euniah Mbabazi, Mwende Kyalo and Jennie Marima to name a few) previously the preserve of employees from publishing houses. Distribution challenges, which have limited the growth of self-publishing, are being addressed by player such as the indefatigable Nuria Store.

I strongly say that the future of Kenyan publishing is in self-publishing. Gone are the days when one had to wait for the gatekeeping publishing executives to get your work out there. Writers like Charles Chanchori, Scholar Akinyi, Lesalon Kasaine, Vera Omwocha, Ciku Kimani, Munira Hussein are good examples of writers who have built audiences of eager readers who want to read for enjoyment and are thriving. And The Book bunk, Kenya Readathon, Storymoja, Macondo Litfest, Lexa Lubanga, and Soma Nami are creating a buzz around the industry. I think the industry is in good hands.

- Your last book, Hawkers Pokers came out two years ago, what are you currently working on?

I wrote another humorous (hopefully) book called Fools Day in 2021, and spent most of 2024 rewriting it based on feedback from my usual group of ‘beta readers’. It is now under review for publication. I hope to have it published in time for the next Wahome Mutahi Prize consideration.

This year I am also restarting work on a more serious novel that talks about state capture and false flag terrorism in an unnamed African country. Let’s see how that goes!

- There was a period you used to be quite active, promoting writing on social media, not so much today…

Is that true? I didn’t think so, personally. But if I am, I blame it on work pressure – the last few years have been busier for me as I settled into a new role and new environment. I do not believe in hiring someone to manage my social media accounts – nobody is able to replicate my voice, and I want my readers to know they are talking to me directly when they do.

Secondly, working in a time zone five hours ahead of me robs me of the opportunity to engage in real time with my fans. My visibility across social media was because I used to respond to as many messages as I could, something I no longer have the capacity to do. But I will continue make every effort to engage with my fan base.

- By now you must be fully settled in Singapore, both career-wise and socially, what would Kenyans learn from that country and how has the move shaped your writing?

There is a lot to learn. I hear a lot of our politicians comparing Kenya to Singapore and calling it the Singapore of Africa. This makes me sad, because Kenyan leaders want Kenya to be like Singapore, without doing the things that Singapore did to be where it is. The government of Singapore thinks of creating a perfect world for the future, decades ahead.

Our leaders do not think beyond their current terms. A lot of them come to Singapore for ‘benchmarking’, which is disappointing because a simple thing as having dustbins available in the city is a tall order. While it rains heavily in Singapore, the drainage system ensures that the flood waters are drained off in a few hours. Tap water is safe to drink in Singapore. Every bus stop in Singapore has a dustbin. What the leadership here has, and what we lack, is Intention.

I am exactly 5 years in Singapore this month, and we can learn a lot about vision, and leadership from Singapore. . Perhaps, one of these days, I will write something longer about this disconnect and what Kenya must do to be the true Singapore of Africa.

I am yet to see how this experience shapes my writing. Who knows? Maybe my next character will come to stay in Singapore. Or will be Singaporean. Or a Kenyan who goes to Singapore and falls in love with a Singaporean girl who is herself a mix between Chinese and Malay. I am already brainstorming!

- What is your advice to budding writers looking up to you as a role model?

The same advice that my mentor David Mulwa has kept giving me, over the years: And that is: “Keep Writing!” Every time I have delivered a copy of my latest book to Mwalimu Mulwa, he has taken it, blessed it and asked me, “So what are you writing next?” The more you write, the more you find your own voice and, consequently, the more confident and assured you should become, just like any other serious undertaking: “Practice makes perfect.”

I’d also urge writers to take a lot of time and energy to build their platform on social media. Apart from allowing you to interact directly with your readers and other stakeholders, and letting you know what is happening “kwa ground”, it allows you to build your brand as a writer. Some of the successes I have had, for example, selling out Of Pawns and Players were aided by great social media presence.

Related to this is the importance of building relationships – both virtual and physical. Readers, festival organisers, publishing executives, editors, printers, book sellers, media practitioners, bloggers – all these have been responsible for my success. Seek to build symbiotic relationships with people (not just what you can get from them, but what to add value to them). Seek out coaches, mentors and accountability partners. You will never regret it.