As a little boy growing up in Limuru, writer Ngugi wa Thiong’o was, one night, woken up by his mother to meet some ‘visitors’. Young Ngugi was pleasantly surprised to find that one of the visitors was his elder brother Wallace Mwangi, also known as good Wallace.

Years back, Good Wallace had escaped to the forest, under a hail of bullets, to become a Mau Mau freedom fighter. Now Ngugi was about to sit his toughest exam yet, the Kenya African Preliminary Exams (KAPE), and his brother had risked capture, even possible execution, in the hands of colonial soldiers or their local home guard collaborators, to come and wish him success in the exams.

The risk was pronounced by the fact that Kabae, one of Ngugi’s many step-brothers, was now working for the colonial forces as an intelligence officer. A few days after Good Wallace’s visit Kabae also visited to wish Ngugi success, or had he gotten wind of Good Wallace’s visit?

Young as he was Ngugi had to learn to live with the conflicting emotions and contradiction in their large family. After all, this was in 1954, two years after a state of emergency was declared in Central Kenya, thereby marking the darkest period in colonial Kenya.

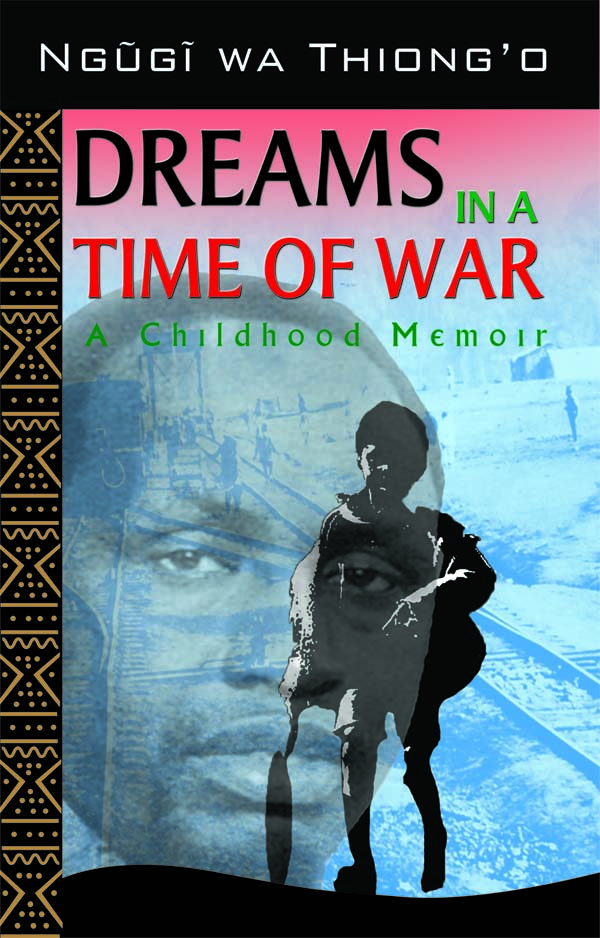

Ngugi, Kenya’s foremost literary personality, captures these experiences in Dreams in a Time of War: A Childhood Memoir. In this book, Ngugi once again asserts his reputation as a sublime story-teller.

With his creative power, Ngugi transports the reader into the mind of a young boy and lets them see things through the lenses of a child. Here, a child’s innocence and naiveté forms part of the narrative.

Only rarely does the grown-up and intellectually sophisticated Ngugi show his hand, in the narrative, often laced with subtle humour. Just as this is Ngugi-the-child’s show the author, as much as possible, lets Ngugi the child do the narration.

Just as a child’s universe is impressionable and full of imagination, so is this book.

Ngugi’s formative years coincided with the rise of African nationalism, which was informed by the participation of Africans the First and Second World Wars. This is where Africans realised that the white man, just like them, was mortal after all. This, in effect triggered the struggle for equal rights by demobilised African soldiers, who felt cheated after not getting land, like their white counterparts.

Then, Ngugi, in his childish imaginations, pictured the early nationalists in larger-than-life dimensions. To him, people like Harry Thuku, and later Jomo Kenyatta, and Mbiyu Koinange, were mythical, even magical characters.

He for example imagined the Germans, who at the defeat of the Second World War, surrendered to his step-brother Kabae, who had gone to fight, on the side of Britain in far off Burma, among other exotic sounding places.

As for Kenyatta, the author’s adoration for the mythical figure was to turn sour, when the man, as Kenya’s first president, consigned Ngugi to detention without trial, in 1977.

Much has been made about how Ngugi, in this book, has shed off some of his controversial views and opinions, but when you put into consideration that at that age Ngugi had not yet formed those opinions, then critics making those observations are jumping the gun.

By the time this book comes to an end, Ngugi has just stepped into Alliance High School for his secondary education, so you do not expect a person at that stage to know, let alone appreciate, ideologies like Marxism and other controversial ideas that make Ngugi what he is today.

Maybe critics, who have made careers attacking Ngugi’s every move, should practice some restraint and wait for that point when he tells how he came to embrace those controversial ideas, and why, only then can they take him on.

Apart from growing up under the horrors emergency rule, the author had other things to worry about. He for example had to go out in search of jobs in other people’s farms to supplement the little income his mother earned.

This was in addition to the fact that at a tender age Ngugi and his younger brother, Njinju, had to endure the ignominy of being chased away from home by their father to go and join their mother who had earlier escaped her matrimonial home to escape her husband’s beatings.

Maybe as a way of escaping from those difficulties young Ngugi sought refuge in books, and especially the Old Testament, which had the effect of transporting him to an enchanting world away from the reality of his suffering. Thus a long-life bond between him and the written word was formed.

And all this was as a result of a pact he made with his mother to go to school and do his best. “Was that the best you could do?” was the constant refrain from his mother whenever he brought home a result or the other from school. It also served to inspire him to work even harder.

By deciding to write his memoirs in instalments, Ngugi took the risk of turning off readers who might argue that there is nothing spectacular about a book dealing exclusively with one’s childhood.

His life was not much different from other children growing up at around the same time and under the same circumstances. But then, it takes a special writer to turn otherwise mundane details of growing up into a highly readable and entertaining book.

Most readers have a rough idea about Ngugi’s life story. They also know that the more interesting and controversial aspects of his life lie ahead of Dreams, which means that future instalments of his memoirs will be highly anticipated.

Maybe for future instalments, Ngugi’s Local publishers EAEP should consider releasing their local edition at around the same time as the American and British editions. That way, EAEP would take advantage of the international hype created on the book to move more copies.