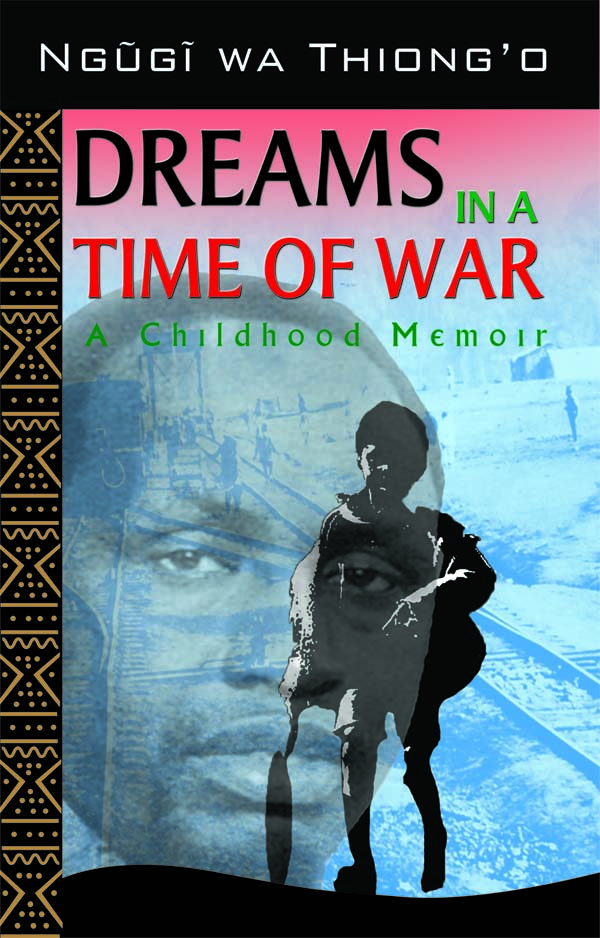

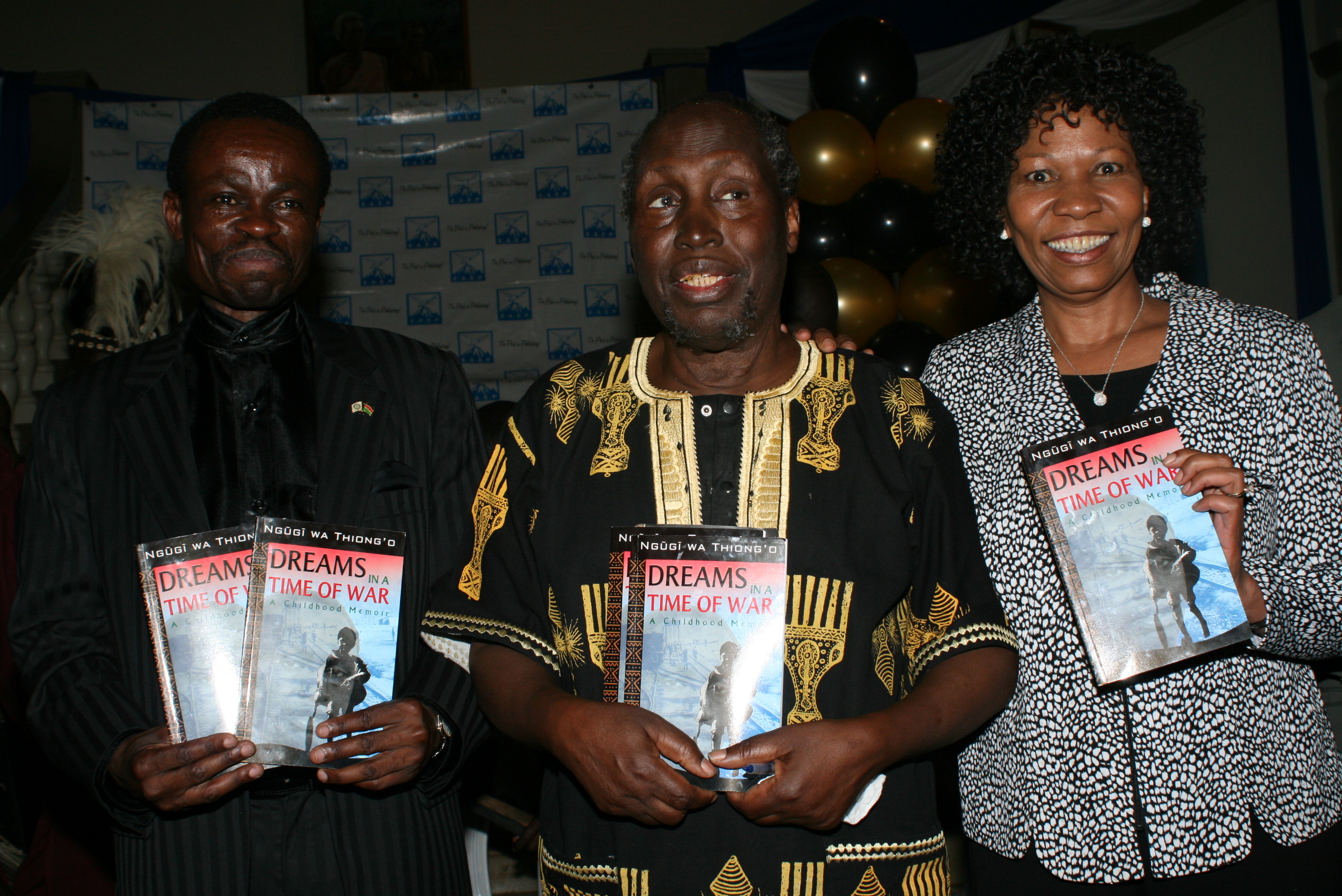

When Ngugi wa Thiong’o was in the country for the launch of his latest book Dreams in a Time of War: A Childhood Memoir, yours truly had a chance to talk with him, and the interview touched on a number of issues. Among other issues he urged young writers not to shy away from self-publishing their works. For a long time the self-publishing route was taken as a last resort, after publishers shut their doors on a writer.

While self publishing is fraught with risks, I think it is time writers gave it a shot. Why am I saying this? Well, as far as Kenyan publishers are concerned, creative works are nothing more than engaging Corporate Social Responsibility. Let me explain: after they have made tonnes of money from publishing textbooks, their conscience pricks them and they decide to do one or two consumer books, as a way of giving back to the society.

The tragedy is that they do not give these books too much thought and therefore do not really market these books. It is therefore not unusual to find good books lying in their warehouses, and they are not being taken to bookshops. Thus don’t be surprised if you walked into a bookstore to request for a Kenyan book only to be told that it is not available. Believe you me, I have been published and I know how it feels for a person to tell you they cannot find your book in a bookstore, including the main ones in Nairobi.

Even when the books are in bookstores, publishers do not bother to make noise about them. Tell me publishers, how do you expect readers – do not give me crap about Kenyans not reading – to know about a book you have published if you do not make them aware of its existence in the market? Is it too much to buy space in the media to shout about your new book?

You see the problem is such that you have become so reliant on the school market to move your textbooks, without breaking a sweat, that you have become complacent.

I recently had a talk with a motivational author who told me that he has moved more copies of a book he self published, than one that was done by a publisher, and in a relatively shorter time. Go figure.

During the interview I asked Ngugi for his opinion on why we are not seeing new novels – not short stories – from young Kenyan writers. Being the good person that he is, Ngugi told me that he did not want to pass “negative judgment” on young Kenyan writers. He urged patience saying that writing is a long process, and that we would eventually be shocked by what these young writers, particularly Kwani? might unleash on us in the future.

I don’t know what Ngugi told the Kwani? crew about our interview, when he later met them, because later that evening at the launch of his book, at the National Museums I was cornered by Billy Kahora, the Kwani? editor, who demanded to know why I had been asking Ngugi “leading questions.” It so happened that Binyanvanga Wainaina, Kwani’s founder, with dyed hair on his head, was nearby and he joined in on the ‘grilling’ . “I just laughed,” Binya sniggered. He was referring to his reaction to whatever Ngugi had told them.

With all due respect, I would love for someone to point out a novel – again not short story – that has been written by the Kwani? franternity, or better still, take a look at this year’s Wahome Mutahi Literary Prize nominees, here and show me a book written by a Kwani? person, and I will show you who is splitting hairs.

You can read the rest of the Ngugi story here.